Introduction

Before feminism, I was interested in sexology, from which I learned that China has an extremely conservative sexual culture and a low overall level of sex education, which not only leads to people avoiding talking about sex in public but also indirectly contributes to the hidden widespread of pornographic culture and, to a certain extent, hinders the timely curbing of sexual violence and crimes.

In 2024, I read Fang Si-Chi's First Love Paradise by Lin Yi-han, which tells the story of Fang Si-Chi, a schoolgirl who is repeatedly sexually assaulted to insanity by her teacher, Li Guo-hua. It led me from sexology to feminism, as I was deeply impressed by the feminist ideas of some readers shared on the digital reading forum I used.

Over the last year, my eagerness to further explore this ideology and social trend kept growing, and luckily, this project offers me what I call a "destined opportunity." Since Fang Si-Chi, I have always believed that the best way to understand a person is to understand her pain; similarly, I think the best way to understand a social trend is to understand its dilemmas, which allows me to take an inside view about the aims and ongoing efforts of it that is uninterrupted by outside voice. Thus, my research on C-femA concept introduced in Wu and Dong's essay (2019), which is short for "made-in-China feminism" (p.4) that differentiates from the Western feminism. was guided by the following question:

In this multimodal composition, I will begin with a brief history of C-fem and then discuss three major dilemmas of 21st-century Chinese feminist movements: anti-feminism and misogyny, party-state control, and marginalization of disadvantaged women. In the end, I will summarize my findings, provide possible solutions, and state my writing purpose and possible future improvements for it.

Historical Context: From State Feminism to Grassroots Movements

To understand 21st-century C-fem, it's always necessary to first examine the historical foundations. Unlike Western feminism, which emerged largely as a grassroots movement against patriarchal structures, C-fem was initially shaped by state policies aimed at mobilizing women as part of broader political and economic goals.

State Feminism Era: the "Iron Girls"

Under Mao Zedong's leadership (1949-1976), China promoted a form of state feminism encapsulated in his famous saying: "Women hold up half the sky." This era saw the promotion of gender equality through labor participation, with the "Iron Girls" representing the ideal of women's capability to perform traditionally male work. However, this state-sponsored equality often neglected the double burden women faced, as they were expected to fulfill both productive and reproductive roles; also, gender equality was often reduced to women’s labor participation and political tokenism.

Reform Era: the Resurgence of Gender Discrimination

The economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s brought new challenges. As China transitioned to a market economy, many of the protective policies for women's employment were undermined. Discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay became more pronounced, while traditional gender norms resurfaced. The 1995 UN World Conference on Women held in Beijing marked a turning point, connecting Chinese women's rights advocates with global feminist movements and ideas, helping spark feminist research and gaving rise to grassroots activism in the next century.

21st Century: Bottom-up, Grassroots, and Detachment from the State

The early 21st century witnessed the emergence of a more diverse feminist landscape in China. With increasing access to higher education and global information flows, young urban women began questioning gender norms and discriminatory practices. The internet provided crucial space for feminist discussions outside traditional state-controlled women's organizations. However, due to the State's repression of unofficial feminist organizations, the feminist movement in recent years has become more of an apolitical cultural form of ideological dissemination.

2007

The definition of "剩女" (leftover women) by the Ministry of Education as “highly educated unmarried women” has sparked heated debate.

2012

The "Occupy Men's Toilets" movement emerged, with women protesting unequal public toilet facilities in cities.

2015

The "Feminist Five" were detained for planning to distribute anti-sexual harassment materials, marking the publicization of the conflict between the Chinese feminist movement and the state censorship mechanism, and since then more systematic repression has begun to emerge.

2017

A leading Chinese feminist group, the Gender Watch Women’s Voice (GWWV), which had posted a message on WeiboA Twitter-like social-media platform in China and one of the most popular platforms, with 230 million daily active users in 2021. to call for a women’s strike to celebrate the forthcoming International Women’s Day, was forced to close their account for 30 days.

2018

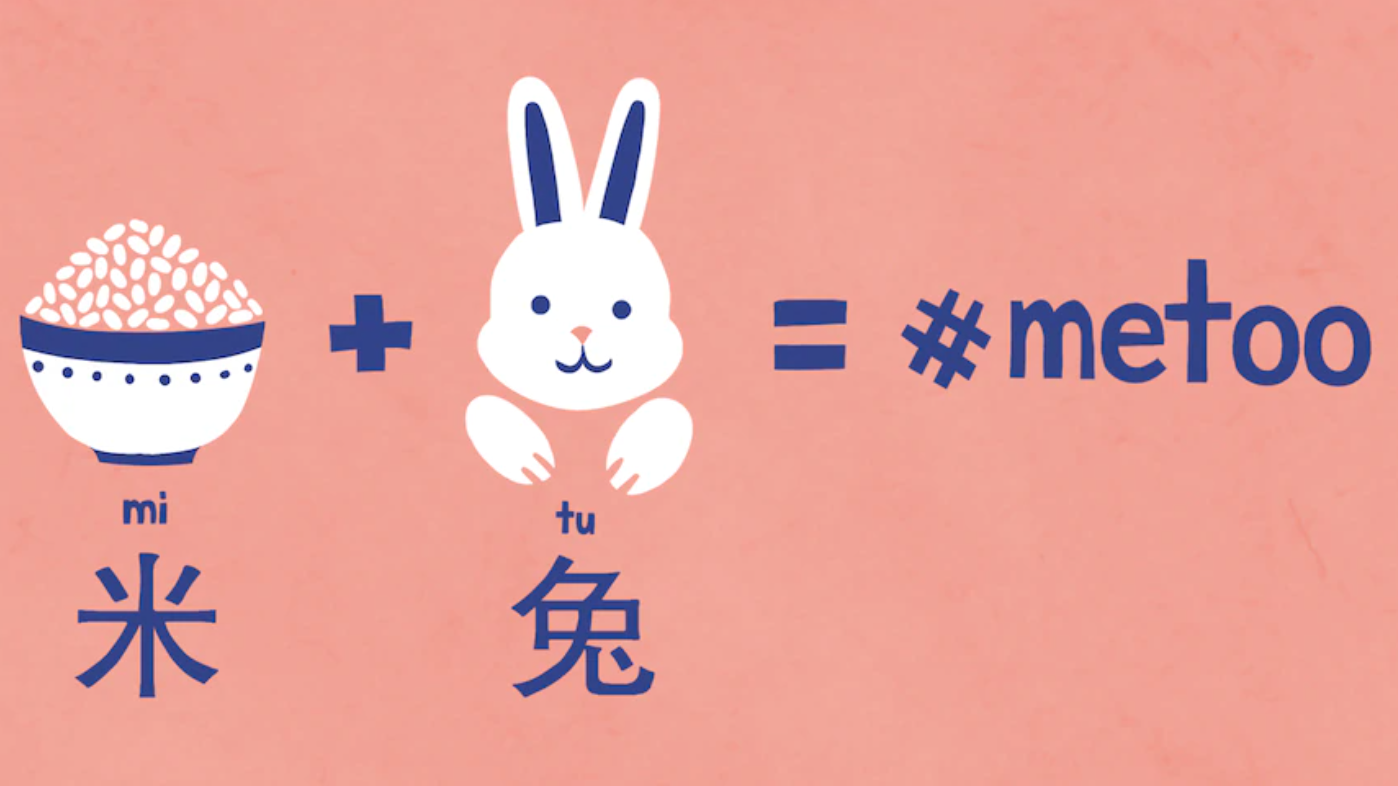

China's #MeToo movementA global campaign against sexual harassment and assault that gained prominence around 2017, empowering survivors to publicize their experiences and demand accountability from perpetrators across industries. gained momentum despite censorship, with university professors among the first to be accused.

2024

"Her Story", a film that realized the dominant narrative from a female perspective, grossing over 500 million RMB and becoming 2024's highest-rated Chinese film on DoubanOne of China’s most influential platforms for film, book, and music reviews, widely regarded as the country’s most trusted source for public cultural ratings., thus triggering a wide-ranging discussion at the socio-cultural level.

Backlash: Anti-Feminism and Misogyny

In 2020, the catchphrase "普信" (average-yet-confident) went viral online in China. It derives from a punchline, "How can he be so average, yet so full of confidence?," delivered by a young stand-up comedian Yang Li to describe women’s experience of men with over-sized egos.

Soon after, on social media, she was accused of "sexism," "man hating," and "provoking antagonism between men and women," and was reported to the National Radio and Television Administration for promoting "sexist" speech. More concerningly, her social media pages were flooded with insults and threats (Huang, 2022, p. 3583).

This incident indicates that while social media provides women and feminists with a space for collective emotional and political expression, anti-feminism and misogyny have also become more acute in such spaces. According Huang's research (2022), she discussed a few strategies that are used by anti-feminists and misogynists to demonise feminists and delegitimise feminism online:

Identifying feminists as deviant women

The most common form of online abuse directed at women feminists involved criticising their appearance, marital status and personality. For example, the following comment was made on an influential grassroots feminist account:

This apparently "banal" but powerful way of demonising feminists—portraying them as deviant women who are not liked by men or are somehow "not women" – is common worldwide. Identifying feminists as "unattractive" is a common sentiment within anti-feminist humour and works to "bolster claims of irrationality" attributed to feminists.

E-bileSame as "electronic bile." A term coined by scholar Emma A. Jane (2014) to describe online messages targeting women that often include misogynistic slurs, threats of sexual violence, and are rooted in broader patterns of digital misogyny.—although circulated in a new medium—merely perpetuates an attitude "with a far older tradition—one which insists that women are inferior.” By side-lining and repelling women who do not follow patriarchal rules, this strategy operates as an attempt to eliminate male’s anxiety engendered by class inequality in the post-socialist transition and re-stabilizes the male-dominant hegemony in cultural changes.

Identifying feminists as betraying the nation

By characterising feminists as obeying the demands of Western anti-China forces (also called "external hostile forces") against China’s renaissance, one anti-feminist (female) posted:

Many prior studies demonstrate that the "Western-rooted" characteristic of feminism is constructed by anti-feminists as an imaginary threat to traditional Chinese moral values and culture, especially when China’s renaissance has been prioritised in the government’s political agenda. This strategy legitimises anti-feminist acts as resisting"imported goods" and forms of neo-colonialism, concealing the underlying political and economic contradictions in society and transferring the blame for structural inequality and systemic injustice onto (feminist) women.

Such xenophobia is, in fact, a manifestation of deep prejudice that demands unquestioning submission to the authority of patriarchy (with women being made nothing more than a resource) and which is intolerant of any deviation from strict rules of conduct (gendered, patriarchal norms). In this sense, the amplification of the ideological Chinese-Western binary is an effective strategy to circulate and reproduce anti-feminist discourse aimed at suppressing feminism.

Identifying feminists speaking online as fake-feminists

The aforementioned strategies show how anti-feminists or misogynists are aligned with other groups—such as nationalists—to form a loose and polycentric alliance. Another strategy has been generated: anti-feminists and misogynists adding prefixes such as "fake," "extreme" and "rustic" to "feminism," constructing two kinds of feminism: "real" and "fake," to distinguish feminists from women who are viewed as "actually" contributing to women’s progress. Data analysis revealed that according to anti-feminists, the "real" feminists who do "progressive" things are figures such as female doctors, entrepreneurs and astronauts. The so-called "fake-feminists" are the "ugly" radicals who oppose national traditions, are in league with Western anti-China forces and Islamists, are only active on social media, and use the "feminist" label to garner unearned advantages. When referring to the "fake-feminists," derogatory terms such as "feminist cancer" and "feminist bitch," and the Chinese homophone "women boxers""女权" (women rights) has the same Chinese pronunciation as "女拳" (women boxing), so "女拳师" (women boxers) becomes one of the most popular stigmatizing tools of anti-feminists on feminists. are used to imply they are brutal and beat up men online. For example, the comments on a Weibo video introducing different schools of (Western) feminism included the following:

These comments lump all feminist ideas online together, as if all urgently need to be suppressed. Yet, studies show that there are many strands of feminism in Chinese online cultures. For example, an entrepreneurial strand, which encourages women to capitalise on their own sexual attraction to maximise benefits in the marriage market. This usually leads to Chinese men’s misunderstanding and criticisms of feminist movements while hybridising stands of feminism in anti-feminist discourse furtherhinders discussions of structural gender inequality.

Moreover, some anti-feminists portray themselves as neutral, objective, and rational—as opposed to online feminists. The data shows their ambivalence: on the one hand, they do not openly endorse gender inequality, perhaps because equality between men and women has the authority of being a fundamental national policy; on the other, in commentary on controversial activism and debates (such as #MeToo) or gender-related news from grassroots feminist accounts, anti-feminist voices are present, loud and clear. What seems to be a contradictory position on the surface, is in fact a subtle way to building collective resistances—being attuned to what people think is reasonable, as well as connecting to cultural norms and particular histories.

To conclude, the abovementioned strategies rationalise and adds creditability to an anti-feminist political agenda to reaffirm the authority of patriarchy.

Party-State Regulation

In November 2018, the Ministry of Education released regulations over teachers’ behaviors, and one rule particularly concerns the strict prohibition of teachers’ improper relationships with students or conducting any forms of sexual harassment. On August 27 2018, a civil law proposal was submitted to the National People’s Congress specifying that a victim may request the actor to bear civil liability according to law, and the employer shall take action to prevent and stop sexual harassment in the workplace in case of sexual harassment through words or actions. Although the bill is not yet legislated and it remains to see to what extent such law can be effective preventions, these are incredible accomplishments for Chinese feminist movements by which anti-sexual harassment discourses and agendas are unprecedently legitimized and echoed by the state power.

The state’s seemingly supportive tone toward the anti-sexual harassment campaign does not mean that the political environment is conducive to feminist movements in China, however.

The political obstacles that the feminist movements (such as #MeToo) face share commonalities with other bottom-up feminist struggles. The coercive state power is attributed to its intolerance over feminism, particularly its critique of patriarchy, and grassroots social movement, which are the main two characteristics of Chinese feminist movements in the 21st century. The immediate attack on them, unsurprisingly, is censorship—including censoring online discussions and monitoring offline actions. Many posts and discussions about feminist activities from Weibo, blogs, and WeChat public accounts were deleted by platforms. Most of the posts with feminist hashtag on Weibo have been deleted by the platform. The blog article that exposed sexual assault by Zhang Peng (a professor from Sun Yat-sen University) by an independent journalist and activist, Huang Xueqin, attracted wide attention and fostered an investigation by that university; but later, the article was deleted by the platform, Netease. Responding to the censorship, activists adopted creative strategies to avoid censorship, including using different hashtags and emojis, and technical tricks.

Despite activists’ resilience, the oppressive political power that the feminist movements faced was rather fierce and destructive. Professor Chang Jiang’s Weibo account was suspended for a month after he started the hashtag #I will be your voice#. A very influential independent feminist media in China, Feminist Voices, was forced to shut down in March 2018. Though it is hard to confirm whether Feminist Voices’ advocating of the #MeToo movement leads to its being shut down, the organization’s strong stance against patriarchy and support for feminist actions evidently make it susceptible to state surveillance and censorship. Feminist Voices’ Weibo and WeChat accounts, with 180,000 and 70,000 followers respectively, were permanently blocked by the two platforms with the justification "violating the related state’s policy and laws." This explanation given by the platforms is commonly used when any posts or accounts are deleted or suspended, and the platform censorship is enacted and legitimized by the state’s Internet censorship with a list of its Internet regulation policies.

Because of the vague explanation offered by the platforms and little response from the government, it is unclear why some posts and accounts were censored while others still remain visible and accessible. But what is certain is that the feminist movements are neither welcomed nor supported by the state. In chairman Xi’s recent statement about women’s development in China, Party’s political power is highlighted: "under the Party’s leadership is of utmost importance to protect women’s rights and pursue gender equality". A statement, as such, indicates that any independent or bottom-up movements, protests, and actions are suspicious to the government as a potential threat to the Party’s political power. Although the majority of posts or actions rarely explicitly critique the state or cautiously avoid doing so, activities related to the movement are constantly interrupted by the official powers, often at the local and municipal levels. Public feminist exhibitions in domestic cities were forcibly stopped and the activists had to find places in foreign countries. Students who organized collective action to demand that universities take action, such as publicizing the process and results of the investigation on professors’ accused sexual assault cases and launching policies to regulate teachers’ improper behavior and relationships with students, were interrogated by the universities and their requests were simply declined.

Marginalization of Disadvantaged Women

In facilitating the #Metoo movement in China, dozens of brave accusers, hundreds of feminist activists, scholars, and journalists, and thousands of concerned publics proactively participate in the online discussions and offline actions against sexual harassment and sexual assault. The participants are predominantly elites, middle-class people, and feminist activists. The prominent visibility lies in the discourse of demanding justice to individuals among high-profile cases and contesting gender inequality.

However, it is observed that both the radical and liberal perspectives in the deliberations and actions overlook the vulnerable conditions of the working-class and rural women. Among the subaltern women suffering from patriarchy, rural and working-class women are even more disadvantaged to the intersectional oppression of the capitalist market economy and urban privilege. Feminist sociological studies have exposed that rural-to-urban migrant women working in factories and households as maids encounter sexual harassment/assault on a routine basis. Rural women in China, among countless women living in rural areas worldwide, suffer from various forms of sexual violence. The lack of institutional support and economic, cultural, and social capital makes working-class and rural women even more vulnerable than urban middle-class women when facing sexual harassment.

Capitalism and rural-urban dichotomy create distinctions between urban, middle-class women and their working-class and rural sisters. Yet, among the discussions of feminist movements on Weibo, Douban, and WeChat, issues about and voices of rural and working-class women are largely absent. There were few deliberations about the sexual violence that rural and working-class women very often face at home in rural villages and in their workplaces, such as urban households and factories.

Such neglect of working-class and rural women is not only about the inclusiveness of China's feminist movements, but also critically relevant to the potential of feminist movements to mobilize the larger masses and pursue broader justice and equality against the interlocking systems of patriarchy, capitalism, and the rural-urban dichotomy in China. Feminist concepts such as patriarchy, gender inequality, and sexual harassment need to be translated into a language that takes root in the lived experiences of ordinary women, rather than abstract ideas. The anti-sexual harassment campaign in universities, media industries, and non-profit sectors are undoubtedly important, but these spot-lighted areas are distant from those women who confront sexual violence in factories, households, and villages. In other words, the feminist movements in China fails to challenge theintertwined inequalities of patriarchy, capitalism, and rural-urban dichotomy.

Conclusion

In the Chinese context, the lack of public understanding of feminism and its meanings, histories, actions, and goals distances the pro-change people from feminist struggles despite their being advocates for gender equality and women’s rights. The hostile attitude towards feminism, be it misogynist or nationalist, creates an unfavorable or even toxic environment where feminists and any participants in feminist activism and movements are subject to violence and attacks. The Party-state’s censorship and surveillance of feminist activism and movements are detrimental to the formation of counter-power against the patriarchal systems. Also, rural and working-class women—who often face routine harassment in factories, households, and villages—are largely missing from the conversation of C-fem movements.

To undermine the interlocking system of oppression in specific contexts, feminist movements should construct more inclusive agendas and adopt various mobilizing strategies to foster greater participation. Moreover, making feminist ideas more comprehensible through campaigning for different cases and strategically navigating political opportunities are essential to extending the feminist counter-sphere to everyday citizens.

By introducing the predicaments encountered by the Chinese feminist movement, I hope to put readers in the shoes of the current feminist movement by discussing its limitations to see the truth of feminism and the feminist movement - always to promote a more equal, inclusive, and beautiful society (despite numerous difficulties).

I also acknowledge that this article does not cover all the challenges faced by the feminist movement in 21st-century China. Other issues that merit further elaboration include the suppression of feminist NGOs, which has pushed the movement toward digital platforms and led to its decentralization; the disconnect between different generations of feminists; and the reluctance of many young people to identify as or publicly voice themselves as feminists due to social pressures.